What do these two novels, written twenty-five years apart by two extremely different writers, one in present tense with references to the past, the other futuristic with insight into the present, have in common? More than you might imagine. As I happened to read the two in tandem, I was struck by common themes, albeit very different treatments.

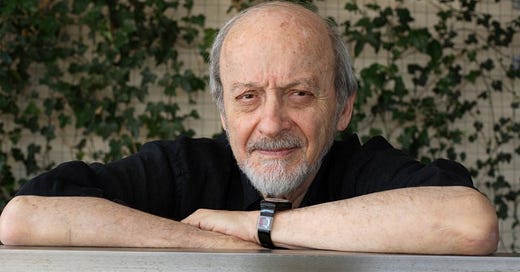

Two of E. L. Doctorow’s many novels have been tucked into my [too tall] pile of backlist TBR. He’s one of my favorites, an award-winning social realist, with magical realism sprinkled in, concerned with the socio-political impact on human relations. Several of his novels have been translated to film and stage, although he often plays with literary structures that don’t lend themselves well to the visual, and which make him all the more original.

[Sidebar] I’ve recently come to believe the great Colum McCann is Doctorow’s heir [see the recent posting on McCann.] Both deploy unique approaches to storytelling and both deeply embedded in the structure of the culture as well as relationships.

You will see how ordinary were my beginnings and how I was swept along like everyone else by the dreadful history of my time. I was without speech for the first three or four years of my life and after that, tongue-tied. Even into my ninth year I spoke slowly, as if dealing with a foreign language, which, as it turned out, I was. What does it matter – all language is a translation from something else and I have lived in that something else for seventy-three years. Doctorow

CITY OF GOD, one of his last works, published in 2000, was not reviewed as well as others, nor is as revered, nevertheless fascinating in its use of alternate voices and forms – poetry and plays within the prose – as well as a profound contemplation of spirituality.

But think for a moment what a shadow portends

The sun is in its heaven,

that’s what that means,

This may not be the world that’s on your string

But this is God’s world, there is goodness there is sin

We have to learn the difference

Again and again.

Doctorow

Who are we, really? Where do we come from, to what do we owe our philosophical, scientific and religious obsessions? Can we rise above our worst selves? These are the questions Doctorow considers in this novel through the essence of spirituality.

Let us imagine such small quiet resentments imploding in the ears of a thousand, a million children of my generation. And a moment later, the Holocaust. For you see what moves not as fast as light but fast enough, and with an accrued mass of such density as not to be borne, is the accelerating disaster of human history. Doctorow

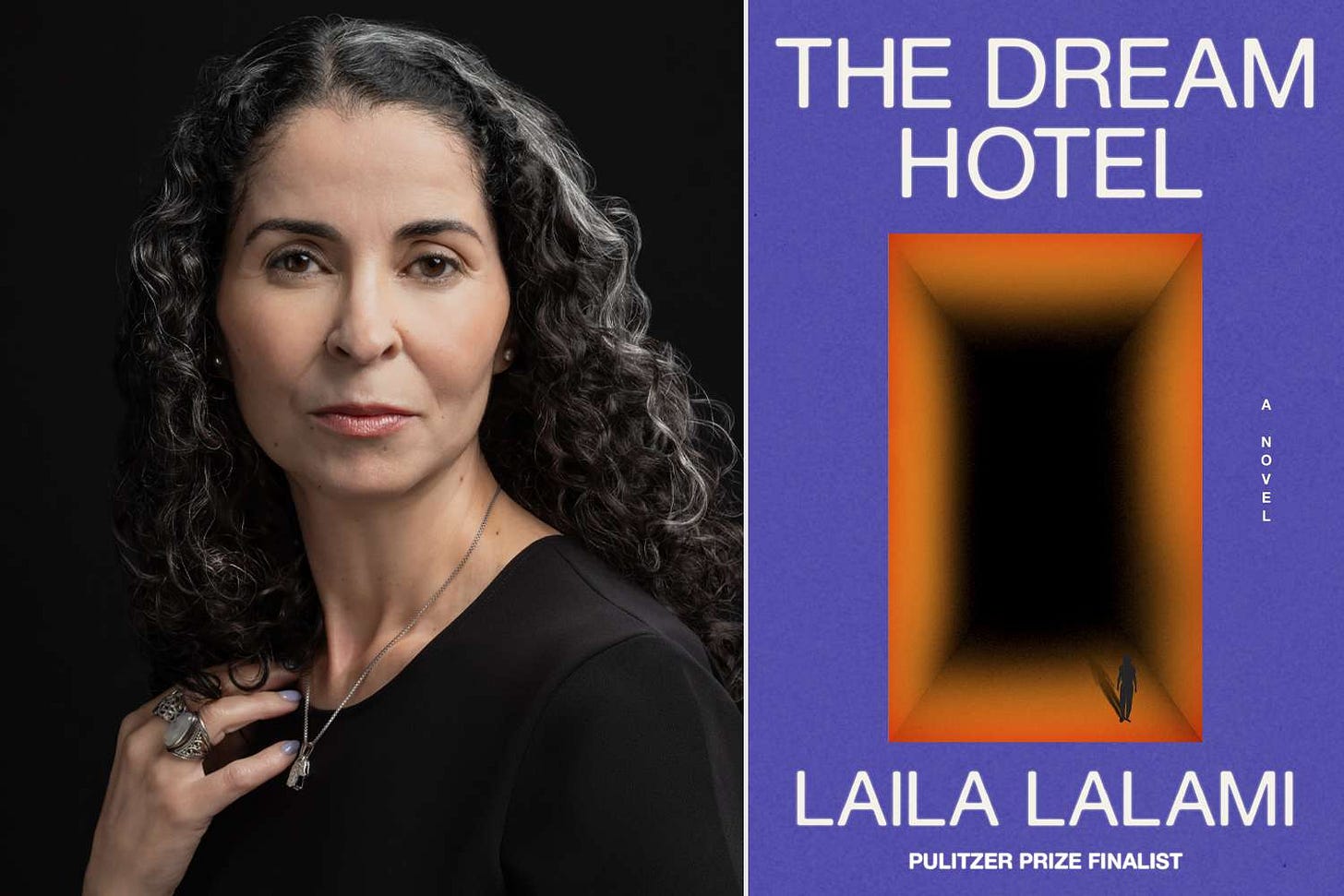

Laila Lalami, a contemporary, award-winning Moroccan American novelist/essayist, has focused her work on her people’s history and the plight of the refugee, which is, of course, inextricably bound to the question of spirituality as well as nationalism. Her new novel, THE DREAM HOTEL, is a departure, in that it takes place in a not too distant future in which artificial intelligence and data mining is used to predict a person’s behavior in a way that crimes might be prevented before they happen. Or that thought might be controlled. Naturally, the system is imperfect and the protagonist is incarcerated mistakenly. Or is she?

Her experience as an archivist had taught her that human error was an inescapable part of any record-keeping program and that it could lead to misunderstandings, some trivial and others tragic. That had to be what happened here. Time was not on her side, thought. Unless the information was corrected quickly, it could become legitimate by virtue of its presence in the records. Lalami

Given the current repressive political climate, her novel is particularly chilling. Who are we really, from what do we derive our deepest thoughts and dreams, and can we rise above our worst, even subliminal inclinations, are similar to the questions in CITY OF GOD, broached differently. Lalami also asks what might we do to protect ourselves from bad players and the potential for a horrific technology-based apocalypse?

That they have committed no crime is beside the point. In any case crime is relative, its boundaries shifting in service of the people in power. Once upon a time, adultery and miscegenation used to be crimes, now they aren’t. Burning flags and collecting rainwater were once legal, now they aren’t. A crime isn’t the same as a moral transgression. The law delineates the former, never the latter. Lalami

If you’ve been short or missed Doctorow, go back to RAGTIME, BILLY BATHGATE, THE BOOK OF DANIEL or WATERWORKS, also his fabulous collected stories. As an introduction to Lalami, I recommend THE MOOR’S ACCOUNT [shortlisted for the Pulitzer] or THE OTHER AMERICANS.

Cheers.